Reported.ly foi uma operação de notícias que cobriu notícias de última hora principalmente em plataformas sociais…

The big business of disinformation

In a world of user-generated content, the battle over public opinion is in the comment threads, not the front pages

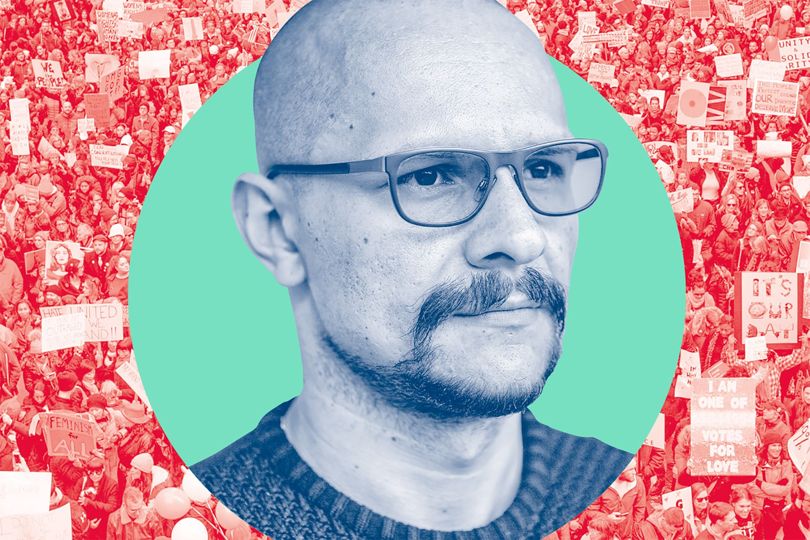

Andrés Sepúlveda (pictured above) spent years working on presidential campaigns in Latin America. Commanding huge fees, the Colombian wasn’t a smooth spokesperson or a rousing organiser – he stayed in the shadows, acting as a political cyberhacker who was hired to influence elections. He claims to have anonymously rented servers in the Ukraine using bitcoin, installed spyware in opposition computers and run fake social-media campaigns. Imprisoned since 2014, he claims to be the master of a world “nobody knows exists but everyone can see”.

The techniques used to sway popular opinion sit on a long, blurry spectrum from the legal to shady to the downright criminal, overt to covert. Decades before Sepúlveda was born, governments in the east and west did whatever they could to influence their own people and those on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In 1964, the KGB secretly published Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy, which alleged that John F Kennedy had been killed with CIA involvement. Forged speeches, planted stories and salacious rumours were all part of the toolbox during the cold war. Stagecraft has long been a feature of statecraft.

States today are not only about sending messages to the public; they are also about pretending to be the public. And Sepúlveda isn’t alone. A global industry has emerged selling over-the-counter digital propaganda. On the dark net, you’ll find the ‘HUGE MEGA BOT PACK’. It’s got YouTube liker bots, SoundCloud auto-likers, Amazon account creators and more. Tweet-AttacksPro, meanwhile, sells software to run thousands of Twitter followers at once. There are services for creating content, making it more visible and more popular, and they range from cheap and cheerful to expensive and bespoke.

No one seems better resourced, more enthusiastic or as accomplished at doing this than the Russians. Andriy Gazin of Ukranian data-journalism group Textura has tracked tens of thousands of linked Twitter accounts that begin pumping out pro-Ukrainian slogans to attract an audience, but over time morph into sources of vicious attacks on Ukrainian politicians. Sometimes these accounts are on autopilot, sometimes a human jumps on to redirect them. Eliot Higgins heads the online-investigation team Belingcat that uncovered evidence of a Russian Buk launcher behind the July 2014 downing of Malaysian Airlines’ MH17 flight. The following year, Higgins was targeted multiple times by Russian hackers. Then, on the second anniversary of the crash, dozens of articles appeared about him on blogs and websites, saying he was a CIA agent and rubbishing his evidence.

Russia isn’t the sole source of disinformation. But there is a particular thread of unreliable information that exploits tensions that are favourable to the Russian Federation: between the EU and the US, the US and NATO and especially between westerners and their governments and the mainstream press.

Western governments aren’t above all of this. The Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group, the British GCHQ internet effects force, was exposed by the Snowden revelations. Its remit included mass messaging, disinformation and discrediting opponents online. But, ironically, I suspect concern about public opinion often holds them back. The blow-back in democratic regimes if intelligence agencies are caught getting up to the really nasty stuff – hounding journalists, sending death threats – is likely to be greater, and the consequences more serious.

The anonymity offered by online media means that there is a corresponding opacity to our measuring genuine sentiment. This matters to the journalists who confuse what’s happening on Twitter with the public mood, to the corporates that measure “buzz” or “sentiment” online to guide their decisions, and the researchers using social media to conduct academic research. But, most of all, it matters to those of us who scan feeds, read blogs and check comment threads. The commercialisation of malign social-media manipulation will continue to grow and be used by state actors. Call it DAAS – disinformation as a service.

Fonte: Wired

Por: Carl Miller

This Post Has 0 Comments